Typhoid

Aka Red River fever.

Disease

In Winnipeg’s early years, serious diseases ![]() like small pox, tuberculosis, scarlet fever and diphtheria frequently reached epidemic proportions.

like small pox, tuberculosis, scarlet fever and diphtheria frequently reached epidemic proportions.

TyphoidTyphoid fever is caused by the bacterium Salmonella typhi. Symptoms include fever, headache, nausea and loss of appetite, along with constipation or diarrhea.

X Close fever was also prevalent in Winnipeg from very early on. In fact, it was once called Red River Fever, since people believed it was caused by drinking untreated water from the Red River.

Health Department, City of Winnipeg. Typhoid Fever Leaflet. |

Council responds

Council initially dealt with health issues through the Health and Relief Committee, later the Market, License and Health Committee. The first report on health conditions in the City was submitted to Council in August of 1874 by Health, Fire and License Inspector, Stewart MulveyStewart Mulvey was born in Sligo, Ireland in 1834. He came to Red River with the Wolseley expedition in 1870. In addition to acting as the City’s first Inspector for Health, Fire and Licenses, Mulvey was a school trustee, an alderman, an MLA for Morris constituency, a member of the Provincial Board of Education, and Grand Master of the Orange Order in Manitoba. He died in British Columbia about 1908

X Close.

Council Communications |

Needs of a Growing City

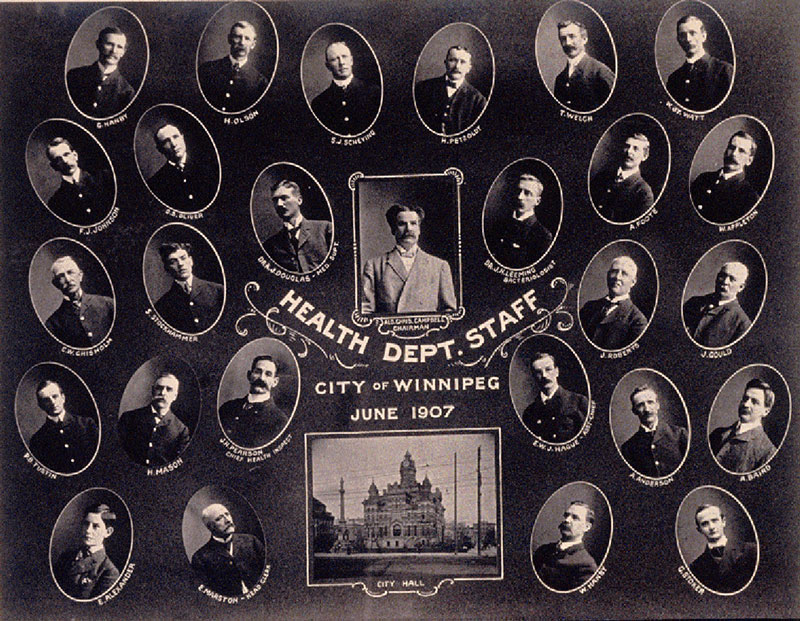

Rapid growth coupled with inadequate sanitation and recurrent outbreaks of disease in Winnipeg required City Council to take a more direct approach to public health issues. By-law No. 1620, A By-law relating to Public Health, was passed by Council in 1899. In 1900, the Health Department was established and a full time Health Officer appointed. By 1905, the City had a Standing CommitteeA permanent committee appointed to deal with a specific subject.

X Close on Health.

Health Department Staff, City of Winnipeg, June 1907 (RO3S26A). |

Fire and Water

In 1904, a major fire broke out in Winnipeg and water from the Red River was pumped into water mains to help fight the fire. As a result, typhoid fever spread to areas little affected in previous outbreaks.

Much alarmed by the increased incidence of disease in Winnipeg, a committee of three doctors of the Manitoba Board of Health prepared a report for Council. They concluded that no amount of effort by Health Department staff would prevent the annual epidemic if box closetsBox closets, outhouses with wooden boxes rather than earthen or brick pits, were a major health concern in Winnipeg because they were plentiful and poorly maintained – their contents tended to overflow and drain into streets and lanes. Statistics in the Chief Health Inspector’s report for 1909 reveal the extent of the problem. In 1905, there were 6153 box closets in the City. By 1909, there were none. However, outhouses with earthen or brick pits were still in use – there were 1485 in total in 1909.

X Close continued to be used in the crowded parts of the City.

Children around a box closet, 368 Jasper Avenue, 1906. (A711 File Misc. 1). |

Concerned Citizens

Citizens expressed concern about dangers to their health by writing letters to Council.

Council Communications |

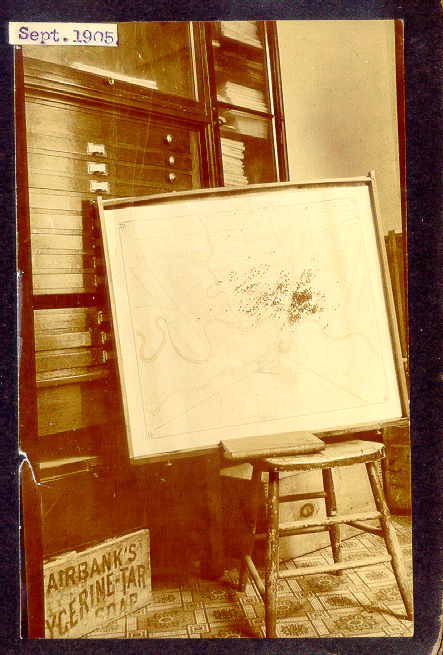

Spread and Concentration

Outbreaks of disease, including typhoid fever, tended to occur most often in the North End where many immigrants to Winnipeg settled. Conditions in this part of the City were cramped, and sewer and water services minimal.

Tracking the Typhoid Epidemic, 1905, one of a series of twelve photographs, one for each month of the year. Committee on Public Health and Welfare (A711 Misc. 1). |

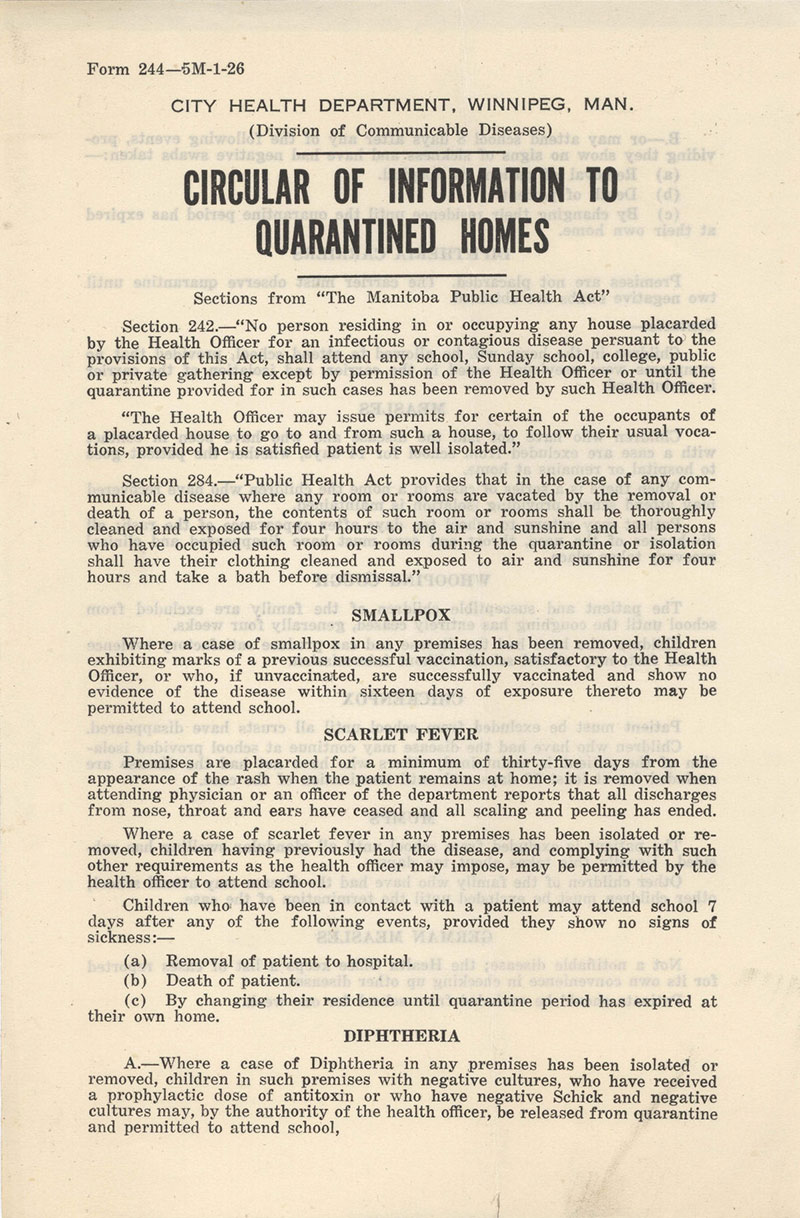

Quarantines

QuarantinesA quarantine may be used when people have been exposed to a contagious illness and may be infected but are not yet ill. Separating exposed people and restricting their movements is intended to stop the spread of that illness. Quarantine can be highly effective in protecting the public from disease.

X Close

were used to try to contain the spread of disease.

Circular of Information to Quarantined Homes. Circa 1905. |

Mayor Thomas Sharpe and Sanitation

In 1905, Mayor Sharpe visited a number of eastern Canadian cities to consult with civic politicians and administrators on public health issues, including water and sanitation, and submitted a report to Council.

Also in 1905, the City called in an outside expert to investigate the City’s typhoid fever problem. Edwin O. Jordan’sEdwin O. Jordon was an Associate Professor of Bacteriology at the University of Chicago in 1905 when City Council invited him to Winnipeg to investigate the typhoid epidemic.

See his report at Winnipeg in Focus.

X Close report to Council suggested that a lack of sewer connections, among other things, had contributed to the high incidence of typhoid fever in Winnipeg in 1904. Council then passed By-law 4143, which required connections for all buildings on streets with sewer and water mains. Council also adopted a motion to allow connections to be made to those who could not afford them immediately by spreading the cost over five years.

As a result of these measures, the incidence of typhoid fever dropped from a high in 1905 of 1,606 cases to an annual average of about 360.

Mayor and Council of Winnipeg, 1906. |

Control and Education

In the 1910 report of the Chief Health Inspector, overcrowding and inadequate plumbing were still identified as contributing factors in the spread of disease. By then, the Health Department was issuing warnings, providing instruction, and using closure notices and prosecutions to clean up the City. Also in 1910, the City commenced publication of a monthly Health Bulletin, noting that "the publication will be a valuable aid to the carrying on of our work which can only attain permanent value by the appreciation and cooperation of all citizens."

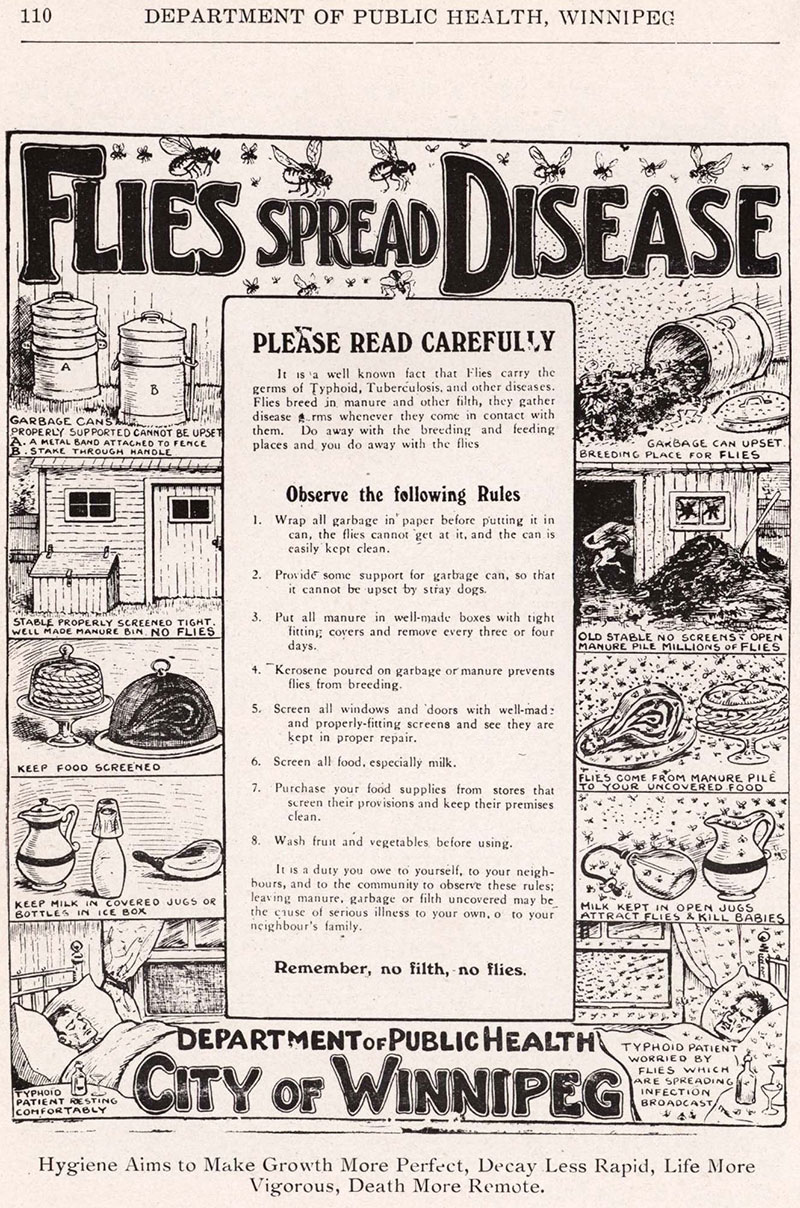

Flies Spread Disease. Poster, reprinted in Annual Report, 1911, Health Department, Committee on Public Health and Welfare (A711 Vol. 1) |