Staff Favourites - Part 1

Selected images from our growing collection of photographs, maps

and documentary art. Check back periodically for new additions.

75th Anniversary Parade

Winnipeg's 75th anniversary parade was held on June 5, 1949, and was a festive affair involving a crowd of over 125,000 spectators. Led by the Police pipe band, the parade was an impressive three and a half miles long. The beautifully crafted floats celebrated historical, cultural, and industrial growth – the official theme of the parade.

When organizers overlooked the industrial aspect of the parade, the Chairman of the Parade Committee, R. A. O'Dowda, pointed out the error. He asked that it be corrected in order to encourage industrial entries. This decision was very much in keeping with past parades that celebrated the role of commerce.

The 75th anniversary parade was the high point for civic parades in Winnipeg. The City's centennial year saw a series of parades organized by various groups, none of which rivaled the scale and splendor of the 75th anniversary parade.

View Waiting for the Parade - a short film on the 75th anniversary celebrations by Paula Kelly.

Graphic used in promotional items created for Winnipeg’s anniversary celebrations, 1949 (Special Committee on 75th Anniversary of Incorporation of City of Winnipeg, File 207). |

Volunteer Monument

This photograph was taken in 1886 at the unveiling of the Volunteer Monument. The monument was erected to honour the men of the 90th Winnipeg Battalion who were killed during the North-West ResistanceAlso known as the North-West Rebellion, the North-West Resistance was an uprising against the Canadian government led by Métis and First Nations peoples in present-day Saskatchewan and Alberta. Key people in this conflict included Louis Riel, Gabriel Dumont, Big Bear, and Major-General Frederick Middleton.

X Close of 1885 – nine men in all.

The events that precipitated the conflict are well-documented in the archives. Read without regard to the larger context of the times, these records – like this photograph – tell a one-sided story about a period in our history during which many lives were lost or forever changed by the pursuit of growth and prosperity. Of further significance is the timing of the monument’s unveiling, which took place less than a year after Louis Riel was executed in Regina and buried without ceremony on the other side of the Red River.

This photograph and related records about the volunteers remind us of the vital importance of viewing archives within a broader landscape of meaning, one that encourages us to reflect upon events in our past and to see them anew.

Ceremonies at Unveiling Volunteer Monument, Winnipeg, September 28, 1886 (P2 File 47). |

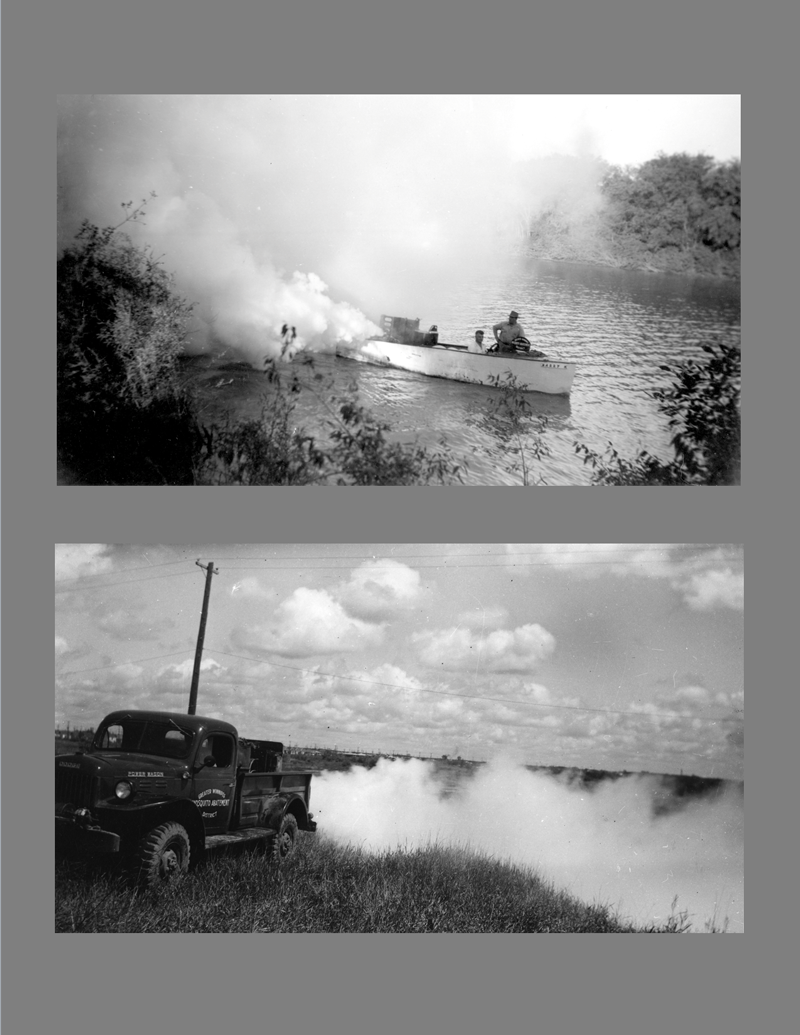

Mosquito Control

In the fifties and sixties, the use of DDTDDT is an abbreviation for the chemical compound dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane.

X Close was widespread. To control the mosquito population in Winnipeg, the chemical was sprayed from trucks, airplanes, and boats.

A report from the Greater Winnipeg Mosquito Abatement District discusses alternative methods for combatting mosquitoes. For example, the District tried pyrethrin capsules, which were made from chrysanthemum flowers. They had limited use, however, as they were costly and failed to rupture on time and evenly disperse. Additionally, officials experimented with placing top minnows in King’s Park. It is not known if the minnows, which were reputed to eat mosquitoes, were effective. Experiments were also conducted using four unspecified brands of detergent.

At first, DDT was thought to be safe, but it was found to be causing significant problems in non-target species. In 1969, the Metropolitan Corporation of Greater Winnipeg approved a report that recommended ceasing all use of the chemical.

Current methods of mosquito control are described on the City’s website.

Fogging for mosquitoes, work performed by the Greater Winnipeg Mosquito Abatement District, 1955 (Parks and Recreation Photo Collection, A67, File 79, Items 1 and 2). |

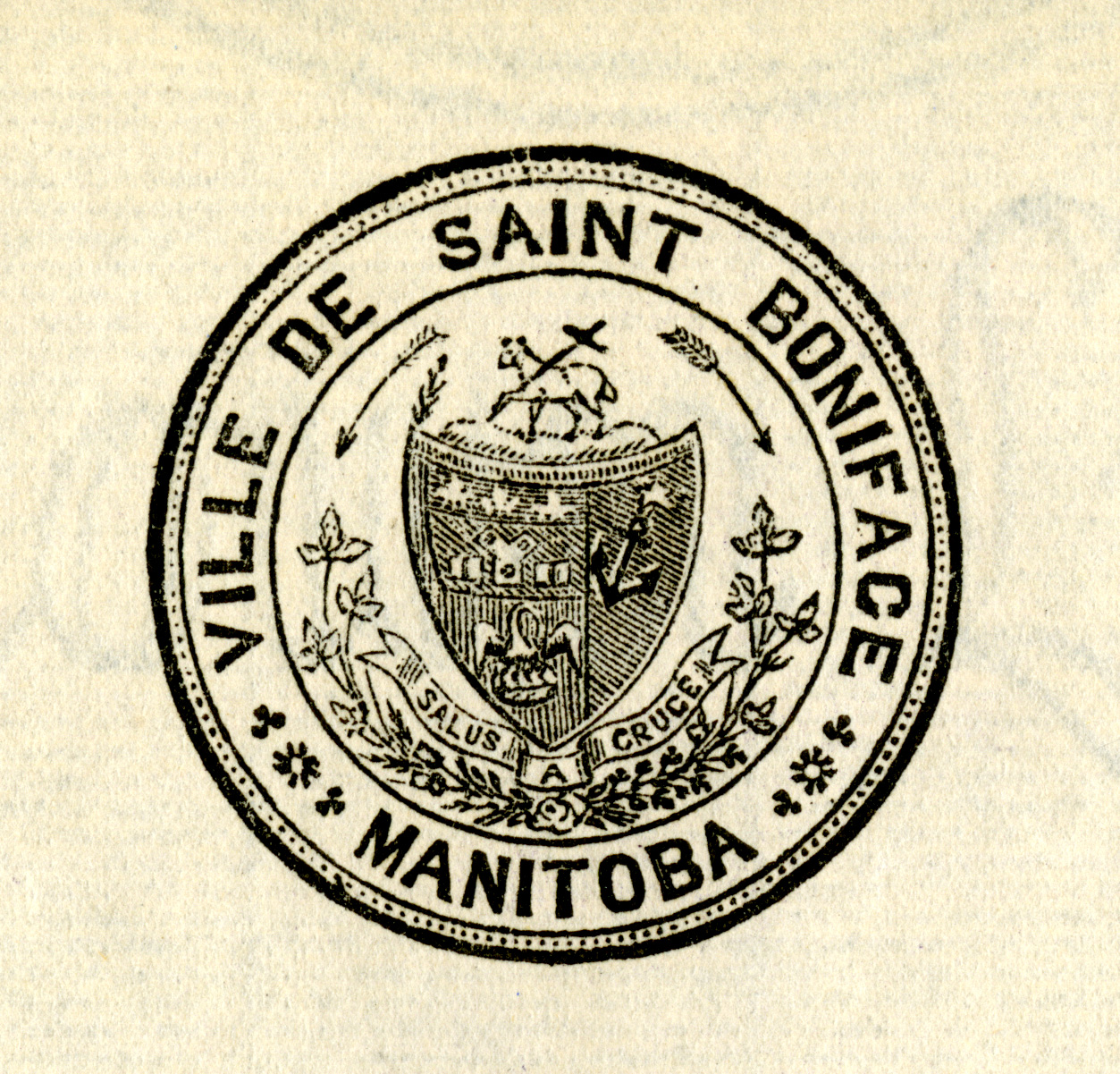

Saint-Boniface Municipal Seal

In addition to making a document official, municipal seals convey a city or town’s history through the use of symbols. From its beginning in 1880 to 1972, the year it joined with the City of Winnipeg, the former City of Saint-Boniface used four different seals – all of them rich in meaning.

The first reference to an official seal for Saint-Boniface appears in By-law No. 16 (1881). The second and most widely known seal for the municipality was adopted two years later. Authorized through By-law No. 8 (1883), the second seal became part of the official letterhead for the City of Saint-Boniface. It was also affixed to documents through the use of a seal press. Whereas the original sealThe first seal is described as a shield divided into quarters inside a double circle: the first quarter holds a golden cross; the second quarter - maple branches; the third quarter - an azure blue Fleur de Lys, and the final quarter - a golden harp. This shield is topped with a beaver in repose on a tree trunk.

X Close showed a beaver, the second featured a lamb holding a cross – an allusion to St. Jean Baptist, patron saint of French Canada. Other symbols, like the thistle, shamrock, and the rose referenced those with Scottish, Irish, and English backgrounds. As well, the arrows symbolized Indigenous community members. Together, these symbols recalled the diverse origins of the people of Saint-Boniface.

Saint-Boniface Municipal Seal (Saint-Boniface fonds, various correspondence). Versions of this seal commonly appear in Saint-Boniface records from 1883 to 1972. |

Saint-Boniface Council Minutes

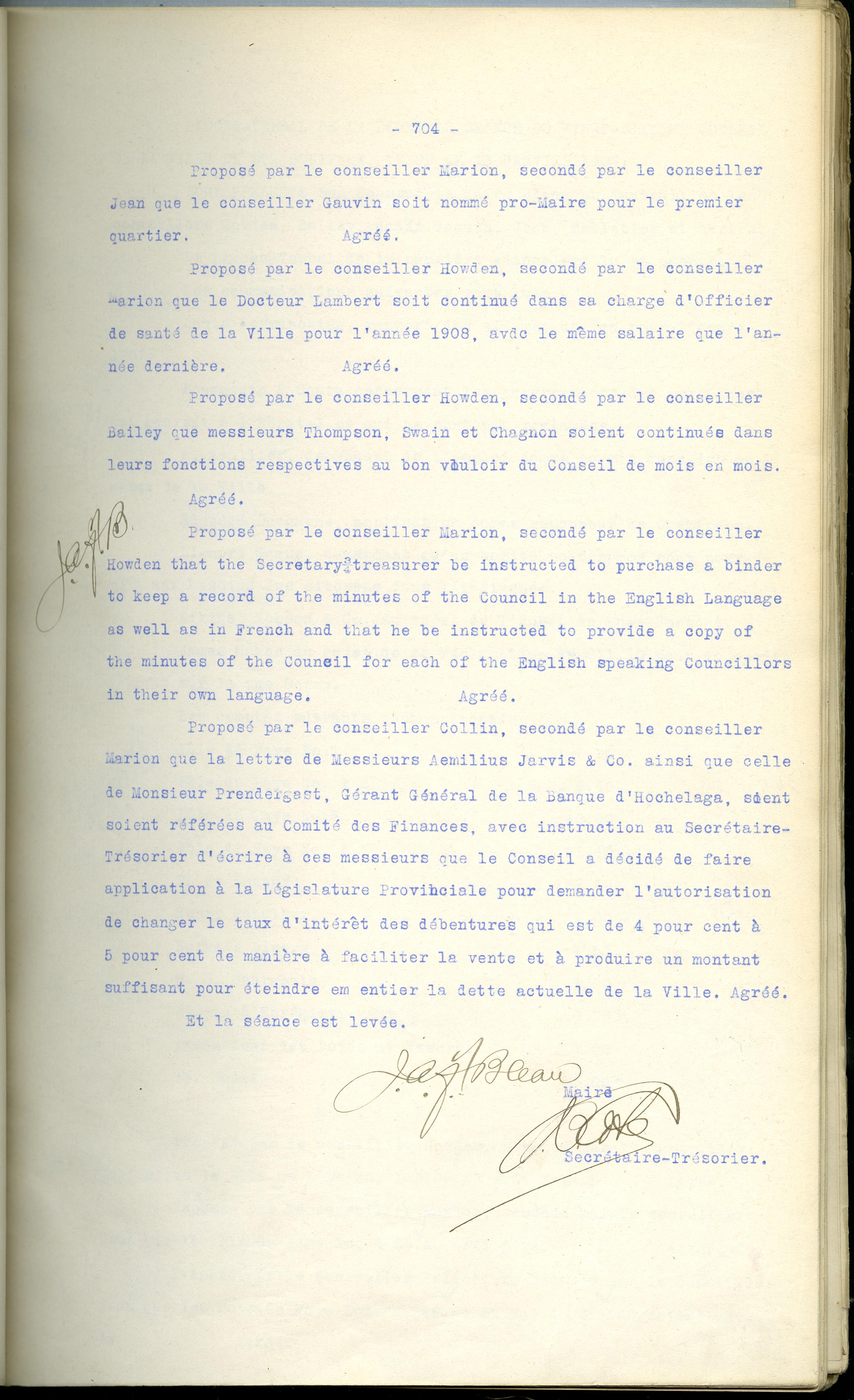

The Council Minutes of the former City of Saint-Boniface document council proceedings from 1880 to 1972. Unlike the other municipalities that amalgamated with the City of Winnipeg, these minutes show that French played a significant role as a language of decision making up until the 1920s. In Saint-Boniface, minutes were not recorded in English until 1908.

In 1908, Councillor Joseph Aldéric Marion proposed that English as well as French copies of minutes be made so that English-speaking Councillors could read them over “in their own language”. The proposal passed, and English copies were made thereafter. The proposal itself was recorded primarily in English, even in the French copy of the minutes. This trend continued, with more and more English being used in French copies, until French copies stopped being produced entirely.

While the collection of minutes held at the Archives represents only what remains of the original minutes, and is not necessarily comprehensive, it nonetheless highlights the challenges Francophones of Saint-Boniface have faced in maintaining their language in civic politics.

Page from the Saint-Boniface Council Minutes featuring Councillor Marion's proposal to record minutes in both languages, January 7, 1908 (Saint-Boniface fonds, A208, File 2). Note the fourth paragraph in which the first sentence begins in French, but then quickly switches to English for the duration. |

Embroidered Badge - 27th Battalion (City of Winnipeg)

Herbert H. Clark came to Winnipeg from England and worked at the Eaton's Department Store before enlisting in the First World War on October 27, 1914. During the war, he was a battalion runner and bandsman with the 27th Battalion (City of Winnipeg)The 27th Battalion (City of Winnipeg) was an infantry battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force that saw active service in France and Belgium during the First World War (1914-1918). Most of the battalion members came from four other Winnipeg militia units - the 90th Regiment (Winnipeg Rifles), 43rd Cameron Highlanders, 100th Winnipeg Grenadiers, and 106th Winnipeg Light Infantry. Mobilized in Winnipeg, the battalion received special permission from City Council to be called "The City of Winnipeg Battalion" and use the City's coat of arms in the design of its badge (See: Council Minutes, April 19, 1915, No. 344).

X Close.

After nearly two years in France, Clark was hospitalized for tuberculosis and sleeping sickness. While recovering at Basingstoke, England, he learnt embroidery and modeled one of his works after the badge of the 27th Battalion. He later affixed the cap badge and greatcoat buttons from his uniform to the piece and placed it in an ornate frame made by a relative.

Clark moved back to England following the war. Upon visiting Winnipeg many years later in 1960, he offered to gift the embroidered badge to the City. In a letter to Mayor Stephen Juba, Clark explained the significance of the work and its connection to Winnipeg. He sent the embroidered badge and a photograph of himself in his hospital cloths all the way from his home in Chippenham, England, to those in Winnipeg who would preserve this important piece of history.

Embroidered Badge – 27th Battalion (City of Winnipeg), circa 1918, City of Winnipeg Archives Art Collection. Photo credit: Mayor’s Office. |