Story Seeds – Part 3: Grounding Indigenous agriculture

Cahokia’s urban Indigenous movement

Cahokia was a North American city that existed between 600–1400 CE, near present day St. Louis, Illinois. During a population peak from 1050-1150, it was home to 20,000 First Nations people. In 1250, it was larger than London, England. In fact, Cahokia was the largest urban centre north of Mexico!

It covered an area of 6 square miles and a variety of earthworks made it unique. The site had at least 120 mounds of different sizes and functions. The most notable was 100 feet tall. It is the largest prehistoric earthwork in the Americas!

Five Woodhenges were used to determine changing seasons and ceremonial dates. These sun calendars were grounded by large, evenly spaced red cedar posts in a circle. Certain posts align with the rising sun at the winter and summer solstices and at the spring and fall equinoxes. The artifacts found here were decorated with sun symbols. The original fragments of this reconstructed ceramic beaker were found near the winter solstice pole.

Through science and engineering, the people of Cahokia planned and predicted successful planting and harvesting of crops. These achievements made the community grow. Large-scale farming provided stable food. It led to specialized work and technology, strong kinship networks, and rich oral culture.

You grow, girl

A range of activities like farming, hunting, trapping, and fishing contributed to a well-balanced diet. To add, the people of Cahokia foraged and gathered nutritious wild foods. They collected acorns and other nuts, and an abundance of wild berries like strawberries.

There were large communal fields, smaller family plots, and small kitchen gardens. In Cahokia, cultivating and harvesting traditions belonged to the Indigenous women farmers. They were part of the physical and spiritual domain of women. The red female flint clay effigies found here were symbolic. They suggest that people appealed to an Earth Mother for guidance through individual acts of self-expression and communal ceremonies.

Pipestone statuettes like the Old Woman Who Never Dies were unearthed here and at other Mississippian sites. The Birger Figurine features a kneeling woman. She wears a bundle on her back and uses a hoe to till the back of a feline headed serpent on which she is kneeling. The tail splits into a squash vine bearing fruit. It’s dated to around the year 1100 CE, almost a thousand years old.

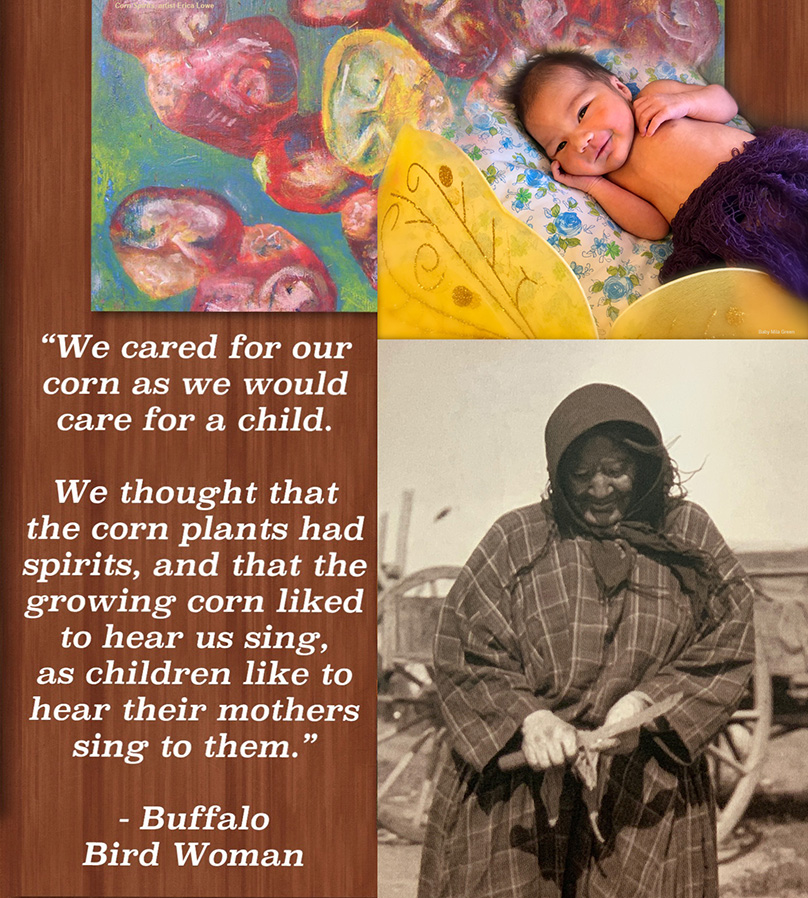

Waheenee, Maaxiiriwia (Hidatsa)

Within many agricultural communities, the fields were traditionally nurtured and maintained by Indigenous women and girls. Their extensive knowledge and contributions ought to be celebrated. Yet, histories of this time typically focus on male-orientated activities, like hunting and war.

“Waheenee,”who was also known as “Maaxiiriwia,” or Buffalo Bird Woman, was a member of the Hidatsa Nation, and she was born in the 1830s. She lived in a permanent earth lodge at Like-A-Fish-Hook village along the Missouri river in present-day North Dakota.

She followed centuries-old farming methods. Together, with the women of her family, she raised remarkable crops of corn, beans, squash, sunflowers, and tobacco. She also nurtured her garden alongside her growing family.

Owl Woman (Hidatsa)

Owl Woman is featured in this archival image. She is standing near her garden on the Fort Berthold Reservation. She is arranging freshly sliced squash rings on a traditional Hidatsa drying rack. After the squash were dried, they were stored in a cache pit with dried corn, beans, and sunflower seeds. Squash is high in vitamin C and in winter, dried pieces were added to soups and other dishes.

“I look back upon my girlhood as the happiest time of my life.” – Buffalo Bird Girl

“Waheenee”(Buffalo Bird Woman) and Owl Woman were prolific gardeners. Their personal experiences are a tremendous source of Indigenous plant knowledge.

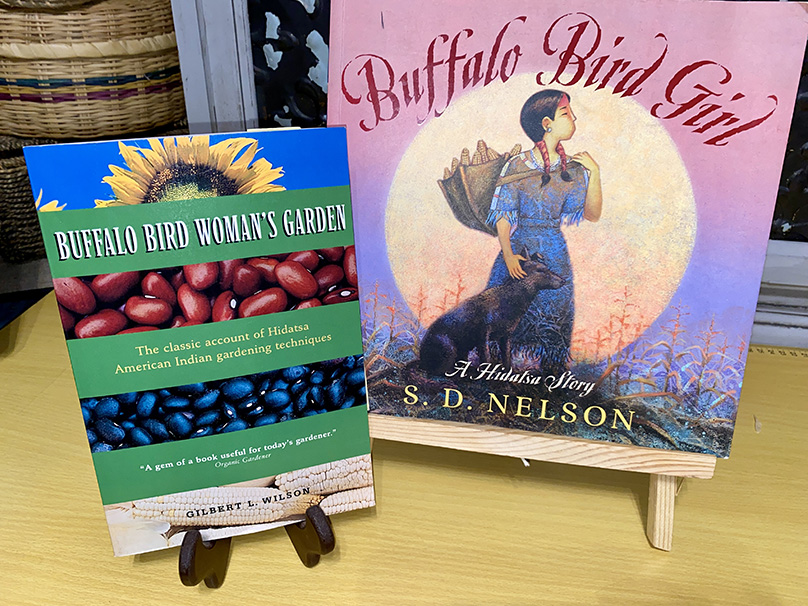

In 1917, many of “Waheenee’s” oral histories were published in a book called Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden. Her son, Edward Goodbird, also contributed to this rich record.

As seen in Buffalo Bird Girl: A Hidatsa Story by S.D. Nelson, her notable character and memories inspire generations of youth. They also inspire knowledge keepers, artists, and gardeners.