Story Seeds – Part 4: Depth of agricultural knowledge

Physical and spiritual domain of Indigenous women and girls

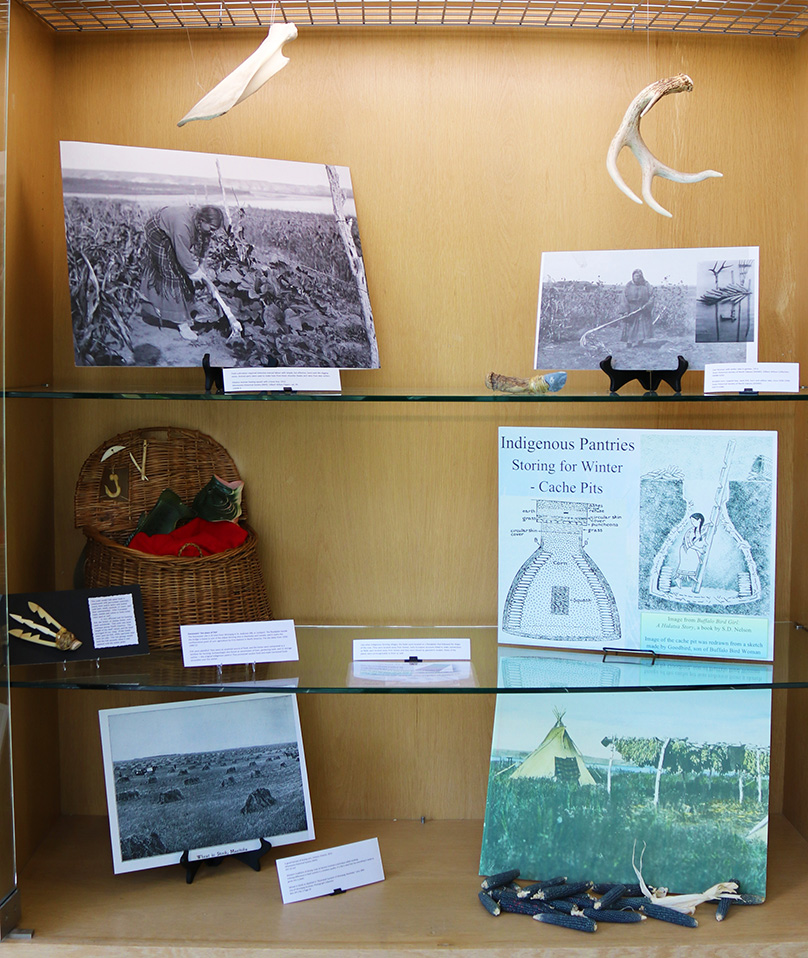

The lifework of “Waheenee” and other women continues to make Indigenous plant traditions accessible. As seen in this iconic archival image, field cultivation required a lot of manual labour. Women used simple, but effective, hand tools like digging sticks. Animal parts were used to make hoes from bison shoulder blades and rakes from deer antlers.

Owl Woman (Hidatsa) is featured in her garden in this archival image, using a traditional Hidatsa rake, made with antlers. Sunflowers and corn plants stand strong behind her.

Corn kernels were stripped from the cob, then crushed and ground on grinding stones and processed into flour for a type of cornmeal mush.

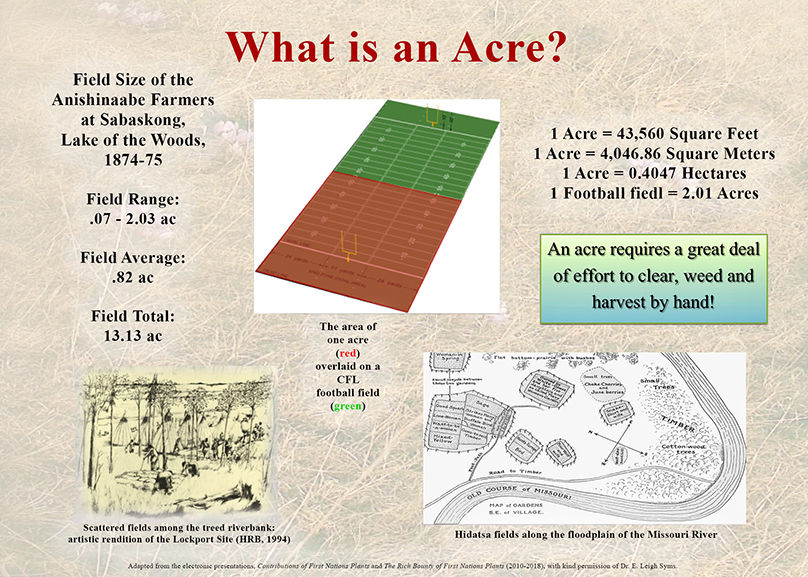

What is an acre?

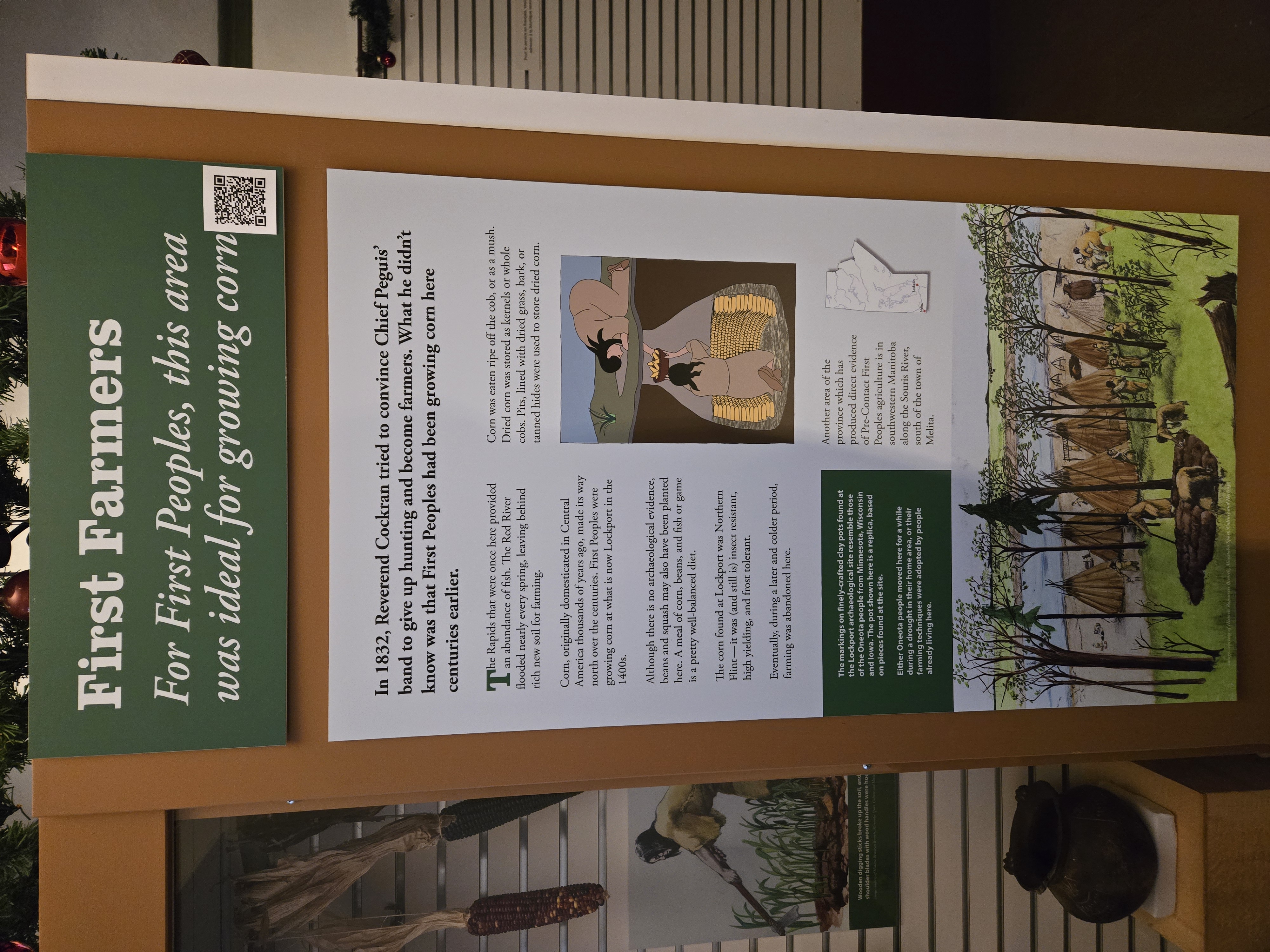

Indigenous farming villages had fields that were on a floodplain that followed the river’s shape. Archaeological records support this. Early European accounts, however, failed to make connections. The fields were located away from homes. Also, Europeans were biased by geometric models and many of the plants were unrecognizable to them.

Kenosewun, “the place of many fish”

Kenosewun Park (or Lockport Heritage Park) is only 20 minutes from Winnipeg at Lockport, Manitoba. The floodplain beside the bridge is home to one of the oldest farming sites in Manitoba and Canada! The site dates from 1350 – 1480 CE. This is 450 years before the Selkirk Settlers. They are often credited for being the first farmers in the area. It also marks the northernmost point of corn agriculture by First Nations in North America.

The Kenosewun site dates back far enough that the cultural affiliation of the First Nation is unknown. However, some of the pottery traditions have been linked to farming cultures of the Mississippi and Missouri River Valleys.

Today, we know how important this area is. It’s in the traditional lands of the Anishinaabe, Cree, Oji-Cree, Dakota, and Dene. It’s in the homelands of the Red River Métis and on the territory of Treaty One Nations. These Nations represent seven First Nations who signed the first of the numbered Treaties. It’s a stone’s throw away from where the Stone Fort and Selkirk Treaties were witnessed by community members.

As the collective stewards of the land and waterways, inheriting this legacy is another gift of "Miskwagama Sipi", the “red water river.”

In Cree, “Kenosewun” means “the place of many fish.” And they were plentiful! Fish were an essential source of food, and the bones were composted as a fertilizer for farming.

Fish hooks: the leister and gorges

A very efficient tool for hunting fish, the leister, or similar forms, were used worldwide.

Gorges were a simple and older form of fishhook. Made from bone or antler, they were designed to be swallowed with the bait and become lodged in the fish’s stomach. They were likely not as effective as the two-part hook, since only a certain size of fish could be caught.

The lack of wood tended to mean that fish hooks in the far North were solid bone or ivory. They were, for the most part, a single piece. One way to make hooks was to carve out toe bones – they have a natural “U” shape with a denser section, for added strength, at the curve.

Variations of bone hooks were used across North America by fishing cultures. Two-part hooks could be found on both coasts, and throughout the interior. They consisted of a sharpened bone or antler spur attached to a wooden shaft (conifer was preferred because it was more water-resistant). They were bound with either sinew or plant fibres, glued using pitch or hide glue, and then coated with pitch or fat.

Surplus at Kenosewun

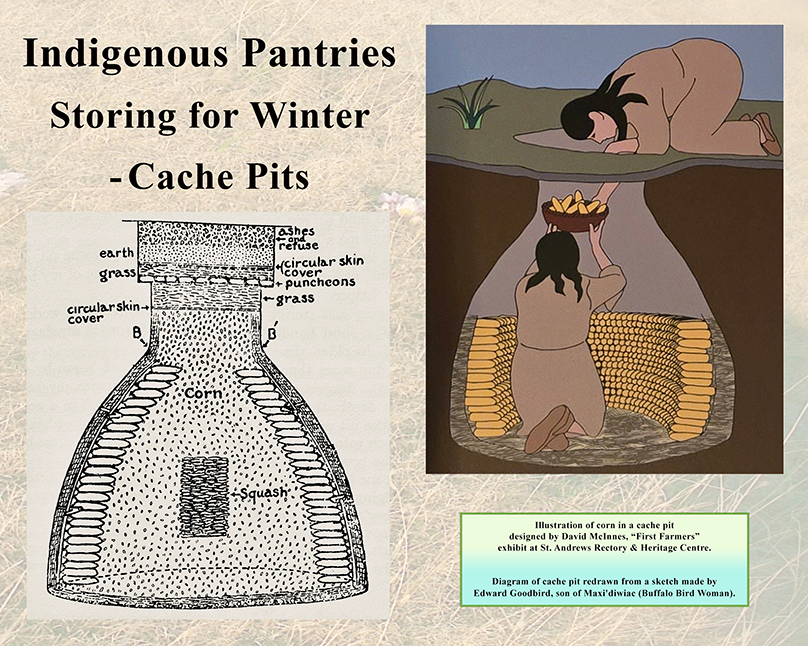

At Kenosewun Park, archaeologists found an assortment of gardening tools. These include 19 bison bone scapula hoes and 12 storage caches. Some of the caches were as deep as 2 metres. This was the original Indigenous pantry!

They protected garden surpluses and made harvested foods accessible over the winter. Food surpluses led to increased populations and more settled lifestyles.

Drying stages

Drying corn involved building wooden stages where the plants were braided and hung to dry in the sun. Pests could also be controlled through this method. This image features corn drying in what was a good harvest near Kenora, Ontario, in 1913.

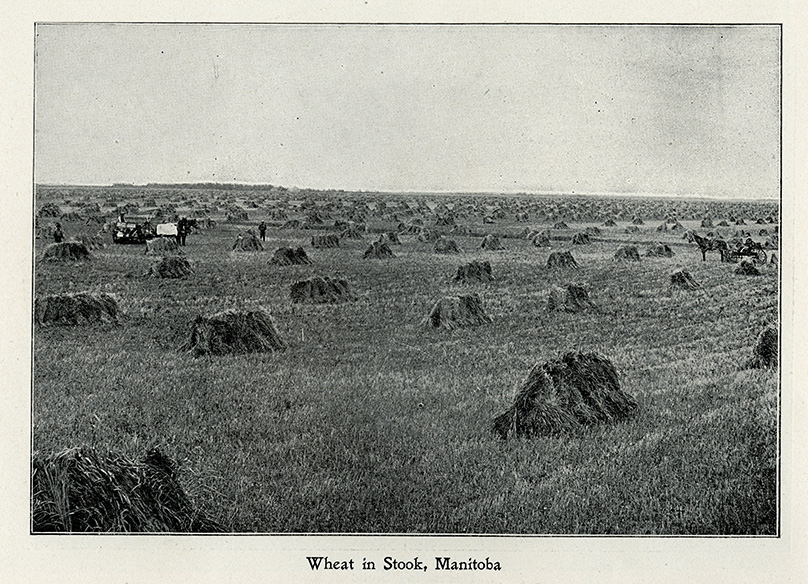

Western traditions of drying crops at harvest involved a technique called stooking. Valuing differences in food systems is a timeless quality. It’s like a seed that has everything it needs to grow into a plant.