Civic employees key part in Journey of Reconciliation

Initiatives aimed to inspire positive change

June 21, 2019

By championing initiatives to create positive change, civic employees in a variety of departments are playing a key part in the City of Winnipeg’s Journey of Reconciliation.

“This is a commitment we take seriously,” said Rhonda Forgues, Manager of the Indigenous Relations Division. “We know there is still a lot of work that needs to be done, but we have seen many examples of positive change within the City.”

City Hall Gardens

Parks and Open Spaces Division gardeners have created two large medicine wheels made of black, red, yellow, and white plants with purple plants in the middle to greet visitors to City Hall.

“I am a very strong believer in reconciliation and I thought the perfect thing would be the four colours of man in the four flowers and also have purple in the centre to represent the creator,” said Carolyn Moar, Knowledge Keeper and Elder.

Two of the City Hall gardens have plants representing a Medicine Wheel.

Since 2016, the gardeners have also planted tobacco, sage, sweet grass, and cedar in two other flower beds at City Hall. The idea of including the four sacred medicines in the gardens came out of the City’s Year of Reconciliation.

“We need to be proud of our heritage, the land we live on, and the people that were here before us,” said Nicole Last, a Parks and Open Spaces Division gardener.

Prior to the gardens being planted, Moar performed a smudging ceremony with the gardeners using the sacred medicines harvested the previous year.

The medicines used to smudge the gardens are grown in the same space the previous year.

“It is incredibly important for our staff to be hands on in the teachings,” said Last. “To have them meet the elder and actually participate in the ceremony connects us all and makes this as important as it actually is.”

City of Winnipeg Archives

The City of Winnipeg Archives was the lead on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Call to Action #77. It requested archives across Canada to identify and collect copies of all records relevant to the history and legacy of the residential school system.

“Winnipeg was actually one of the few cities to have a residential school located within city limits,” said Sarah Ramsden, Senior Archivist. “That was the Assiniboia Indian Residential School so we had some communications between the City and the school.”

The Assiniboia Indian Residential School was located on Academy Road and operated from 1958 “ 1973.

This invitation was declined by then-mayor Stephen Juba.

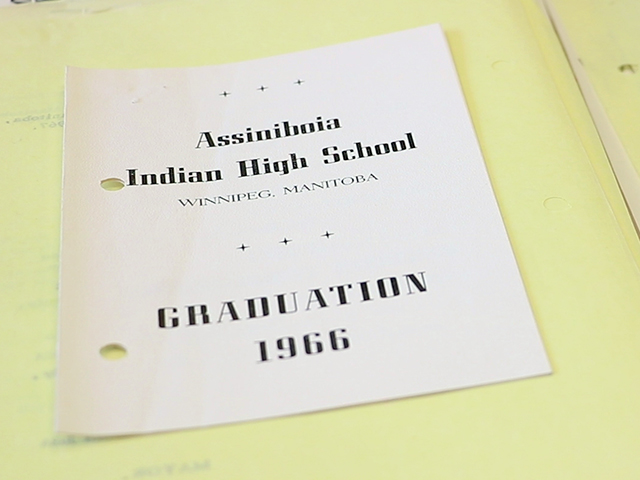

In addition to correspondence with the school, Ramsden found an invitation then-mayor Stephen Juba received to attend the school’s 1966 graduation. The invitation was declined.

Photos from the Greater Winnipeg Water District were also identified as part of the Call to Action. They show children on boats going to the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School. The school was originally located near the intake of the City’s aqueduct at Shoal Lake.

This image shows children on boats going to the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School near Shoal Lake.

In all, around 120 scans totaling nearly nine gigabytes of digital material were provided to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation for inclusion in their collection and projects.

Archives then created the Indigenous Peoples and Records Guide to Research. The guide is designed to support awareness of the history of Indigenous peoples in Winnipeg and assist research in this area by identifying records and contextual information related to seven topics: the urban Indigenous population, settler colonialism, building relationships, Indian Residential Schools, the aqueduct, family history, and Indigenous achievement.

“I am proud to be a part of a workforce and an organization that sees reconciliation as a priority and wants to work towards creating respectful relationships,” said Ramsden.

Assiniboia Residential Indian School Display

When Murray Peterson wrote a report in 1999 about the building at 615 Academy Rd., he briefly mentioned it once housed a residential school. It was decades later the Historical Buildings Officer with the City dug deeper beyond the bricks and mortar.

As part of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, he was asked to research the building’s history. The information was used to create the Assiniboia Residential School Exhibit, a nine panel display aimed to educate employees and residents about the school.

Peterson met with the students and survivors to learn their stories and hear firsthand about what happened at the school.

“We wanted to tell the story and it was going to be through the words and pictures of the students themselves,” said Peterson, adding they had the final approval of the exhibit.

The exhibit, which has two copies, travels to different libraries as well as City workplaces. Peterson hopes the exhibit will help people learn about an important part of Canada’s history.

A National Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former Residential School students. Emotional and crisis referral services can be accessed by calling 24-Hour National Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419.